The book proposes specific solutions to public policy issues pertaining to online privacy and security.

Requiring no technical or legal expertise, the book explains complicated concepts in clear, straightforward language.

Unauthorized Access: The Crisis in Online Privacy and Securityis available for purchase onamazon.

Below is the 11th chapter from the book.

A real-time data feed allows stores to tailor their sales pitch to your path through the mall.

(You were just in Abercrombie and Fitch; we have better prices.)

Among other things, you agree to wear the unit and to permit the data collection.

Additional pieces of paper assert your assent.

By the time you leave the mall, you are covered in tracking devices.

You return all of them except for the virtually invisible microscopic devices attached to your credit and debit cards.

They will track you during your next visit to any shopping mall.

We are, however, tracked in a very similar way on the Internet.

*

Some people take a stab at prevent the tracking, but almost all acquiesce.

Ignorance and a lack of obtrusive guards ease the acquiescence.

Our compliance is a boon to business.

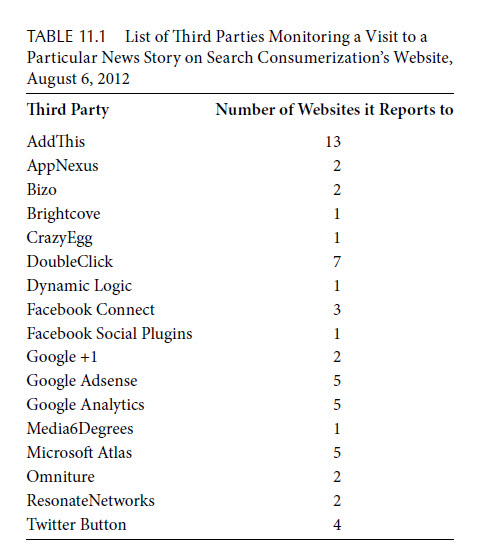

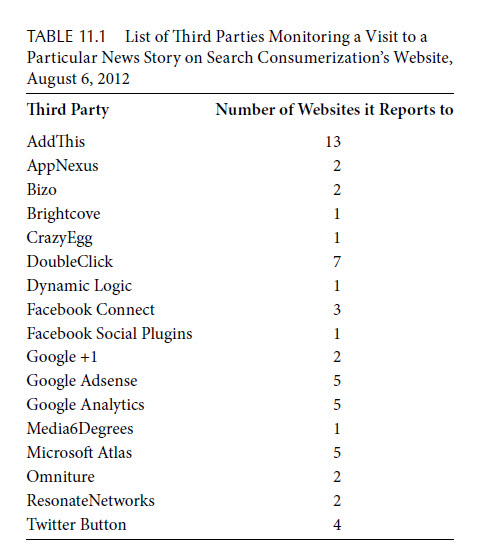

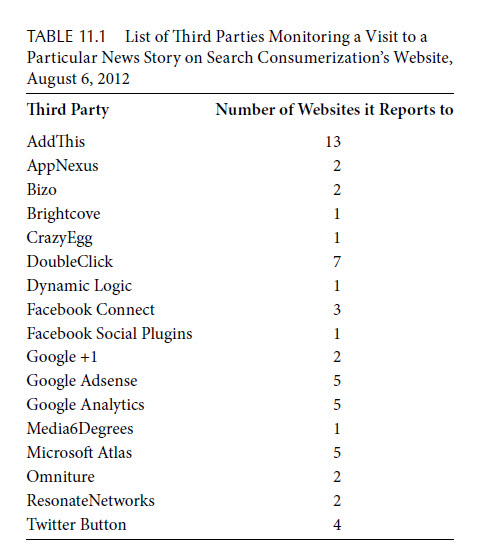

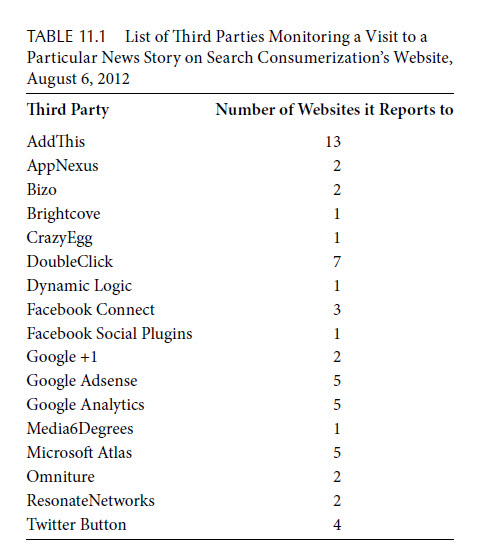

Still, it is quite impressive that AddThis reported back to 13 different URLs.

Big data promises big benefits.

The downside is a loss of informational privacy a massive loss of control over what others know about us.

We consider more of the deluge in the next chapter.

Here, we focus exclusively on behavioral advertising on websites.

We proceed as follows.

First, we will say a little bit about the overall online advertising ecosystem.

We conclude the chapter with a discussion of the legal devices equivalent to the contracts the guards handed out.

Then, in the next chapter, we discuss what how we think things should change.

It combines these data with data from offline sources.

Based on their own claims, this is simply not true.

The tags make it possible to recognize multiple visits as all coming from the same user.

On the Internet, there are several ways this can be done.

You Identify Yourself Using a Login ID We start with the obvious.

If you create a user ID with a website and log inusing that ID, then you are identified.

The same holds for any online shopping website where you make a purchase.

Moreover, all websites where you create a login name that you reuse know whatever information you provide them.

It can be difficult to avoid reusing a login name.

Many, many more sites either require you or strongly encourage you to enter.

A unique login ID is the very best sort of information, because it definitively picks out one individual.

We should emphasize that every really means every in this case.

Now is a good time to explain more about how the mechanics of the web and cookies work.

(Sometimes a more secure variant, HTTPS, is used.

HTTPS is basically HTTP plus encrypting the contents of the packets.)

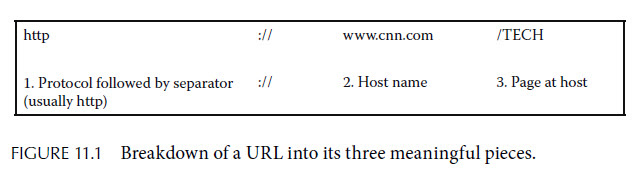

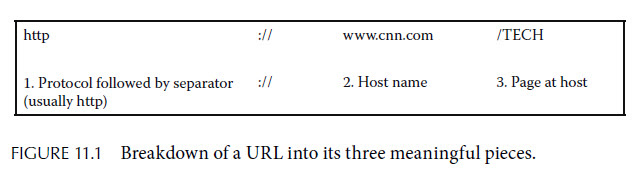

Consider the URL http://www.cnn.com/TECH, which currently is the web address of the Technology section of CNN.

As we show in Figure 11.1, a URL can be broken into three parts.

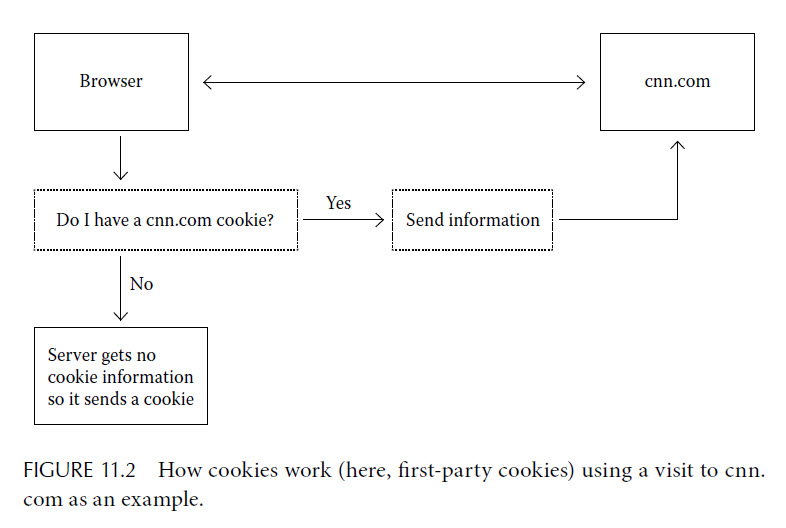

Cookies are part of HTTP.

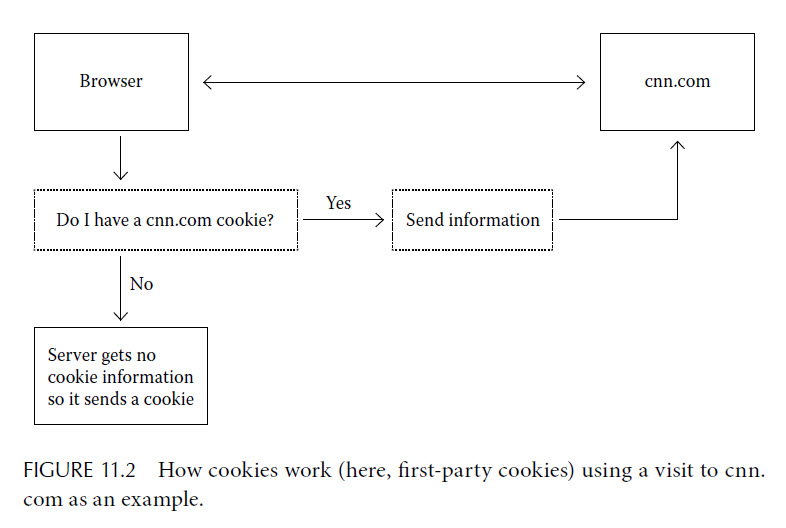

We illustrate how cookies work in Figure 11.2.

Any cookies you get from the host you visited (CNN in our example) are called first-party cookies.

Most or all of the benefits consumers get from cookies come from first-party cookies.

A typical web user who never erases cookies might have many thousands of cookies on his computer.

How does it happen that some websites cause dozens of cookies to be deposited on your gear?

A small part of the answer is that multiple cookies can be a convenience to a website.

So www.cnn.com might deposit as many as 15 cnn.com cookies on your computerrather than just 1.

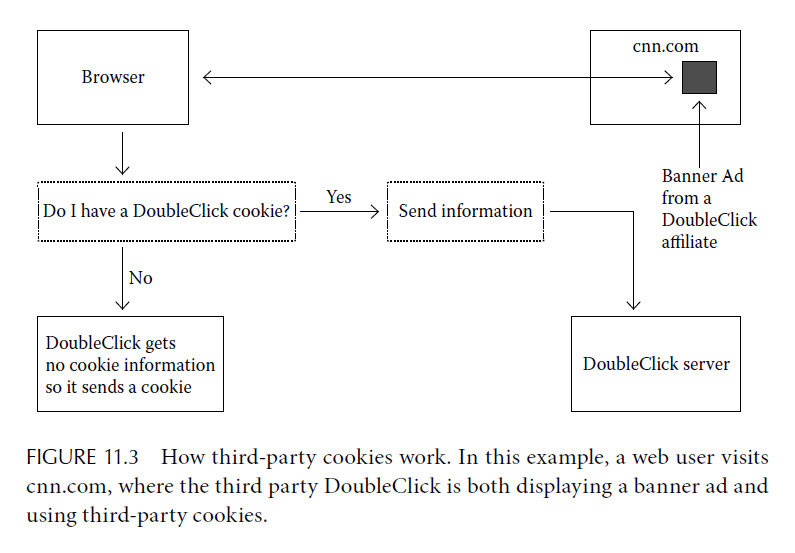

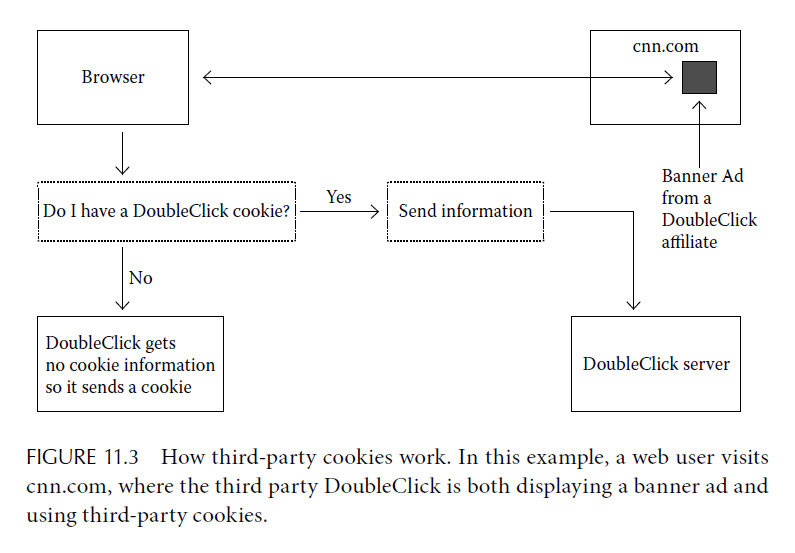

Those websites can also leave cookies on your system, and they are referred to as third-party cookies.

We illustrate this process in Figure 11.3.

It is quite common for major websites to allow multiple trackers to gather information from their website.

A majority also had Omniture, a web analytics data pipe.

In the past several years, a new kind of cookie has come into play: Flash cookies.

The major web browsersall give users the option of not accepting cookies and of deleting specific cookies.

Finding LSOs requires digging into obscure prefs or using special-purpose add-ons to your web net net app.

One use of LSOs is to defeat attempts to delete cookies.

Some users may even have set their web browsers to reject third-party cookies.

The details of cookies will likely continue to evolve.

Furthermore, each piece of information is detailed.

For starters, we should mention smartphones.

Moreover, smartphones know where they are located.

This geographic information too is, in principle, available to every app running on your smartphone.

Recall our discussions of deep packet inspection back in Chapter 8.

What is Wrong with Behavioral Advertising?

Whats wrong with it?

The basic problem is that businesses deprive buyers of choice about how businesses will process their information.

Information processing is not.

It does not vary to conform to the privacy preferences of individual buyers.

The vast majority of buyers acquiesce in information processing practices, thereby guaranteeing sellers significant advertising revenues.

That expectation would be disappointed.

Sellers do not break the moldnot if they rely on advertising as a significant source of revenue.

These are the online equivalents of the pieces of paper the guards and stores presented in our opening metaphor.

Their reaction makes good sense.

The answer lies in two key differences between the offline and online cases.

To take two quite different examples, first consider news websites.

All of these websites potentially collect information, since all of them make some use of third-party cookies.

This is true even for sites like Audacity.

Such exchanges are characteristic of contractual relations.

Second, usually the user doesnt know that he or she agreed to anything.

Billions of such pay-with-data transactions occur daily.

Pay-with-data exchanges are an instance of no-negotiation, one-size-fitsall contracts.

The legal literature refers to this as standard-form contracting.

So why not fix what is broken?

But then the advocates often assume that contracting should go in the trash bin of useless tools.

Contracting is just broken, not useless.

To do so, we need to understand what makes contracting work well in the non-Internet world.

Our answer appeals to value optimal coordination norms that limit what contracts can say.

Mention of contractual norms may suggest negotiation norms, like Do not deceive the other party.

Instead, we are concerned with contractual normsthe norms that apply to the content of the standard-form contract itself.

Such norms answer the question, Should this punch in of contract contain a particular punch in of term?

This allocation of risk reflects the best loss-avoider norm we discussed in Chapter 6.

The second-order norm is the term-compatibility norm: Buyers demand contractual terms compatible with relevant value optimal norms.

We discover violations of the term-compatibility norm by detecting incompatibility with other norms.

Those normsthe first-order norms include the informational, product-risk, and service-risk norms discussed in earlier chapters.

Her behavior is entirely rational.

But Barbara has no need to read the contract.

In Chapter 4, we used the Cayman Islands vacation example to make the point.

When you are on the islands, you have to eat the food that comes with the deal.

Your budget leaves you no choice.

Our point was that this constrained choice is part of an overallfreely chosenplan.

The same point holds for Barbara.

(Even many law school contracts professors rarely read such contracts.)

The standard-form contract is the perfect solution.

Backing out is the last thing she wants to do.

*

This is how things work when the term-compatibility norm is in place.

One way to be compatible with first-order norms is simply to adhere to those norms.

The refrigerator motor, door, and shelves example we used earlier illustrates the point.

It is unlikely that the terms violate standards articulated in cases and statutes.

Now there is a problem, one many have pointed out when we have presented our view of contracts.

People object that our view is implausible because contracts routinely contain terms that are clearly inconsistent with relevant norms.

So how can the norm be that contracts contain norm compatible terms?

Our answer is that we do not equate compatibility with straightforward adherence to norms.

Norm-inconsistent terms cans still be norm-compatible terms, as we will now explain.

Norm-inconsistent terms are still compatible when they do not completely overturn the norm-implemented trade-off but just fine-tune it.

The fitness norm is a good example.

This shift merely fine-tunes the fitness norms risk allocation.

No production process is perfect, so there will be some unfit products on the market.

But these will be relatively rare.

Those buyers pay for the protection they do not need, thereby subsidizing protection for risk-averse and high-risk buyers.

Disclaiming the fitness warranty avoids the subsidy.

Our view is that this fine-tuning is a value optimal adjustment of a value optimal norm.

Legally speaking, the contract disclaims the warranty of merchantability, which is a legal implementationof the fitness norm.

Why should anybody think the fundamental norm governing standard form contracts is the second-order, term-compatibility norm?

Our answer: the term-compatibility norm is a consequence of the existence of first order norms.

We will also make assumptions about what sellers know, but wewill specify those later.

We also add a second ideal condition in addition to the perfect competition condition: contractual norm completeness.

In the real world, compatibility is often a matter of degree.

We will show that sellers will replace incompatible terms with terms compatible with value optimal, first-order norms.

We divide the argument into the part primarily about buyers and the part primarily about sellers.

Perfect information ensures that they know which sellers offer compatible terms.

Profit-motive-driven sellers will do so since buyers will not otherwise buy from them.

The result is that buyers demand terms compatible with value optimal norms is a behavioral regularity.

The argument is the same one we made about the best practices software norm in Chapter 7.

Real Markets: How the Coordination Norm Arises

Real markets only approximate our ideal conditions.

The argument repeats the argument in the ideal market case with adjustments for reality.

We begin by adjusting for real contracts.

The fewer applicable value optimal norms there are, the more terms will remain in the contracts.

We need enough value optimal norms to avoid this result.

We assume that we have them.

In this particular case, it is worth noting that many markets do fairly closely approximate contractual norm completeness.

We begin by noting that buyers prefer to buy from sellers offering terms compatible with value optimal norms.

In ideal markets, perfect information entailed that buyers knew which sellers offered compatible terms.

But we dont really need buyers to know perfectly which sellers offer norm-compatible terms.

We just need buyers to find out eventually when sellers do not.

Buyers will prefer to buy from the rest, the norm-compatible sellers.

Buyers detection of norm-compatible sellers will be imperfect, so the rest will also include some norm-incompatible sellers.

The better detection is, the fewer norm-incompatible sellers will escape detection.

We will assume very few.

Preferring to buy from norm-compatible sellers is one thing; actually doing it is another.

Everything else being equal, you might prefer to buy from Jones over Sam, but things arent equal.

We note in passing that the assumption is plausible for a number of markets.

The costs involved in switching from one Amazon Marketplace seller to another are not particularly great, for example.

Most sellers will know that.

In real markets, most sellers will know that some buyers know when contracts have norm-incompatible terms.

It seems the real markets argument is in trouble.

Since those sellers would be unable to sell at all, the profit-maximizing strategy was to offer norm-compatible terms.

Our strategy involves resolving this issue through redefinition.

While this may seem like an evasion, it’s not.

Mass-market sellers cannot reliably discriminate in this way, however.

The result is not just a norm, but rather a coordination norm.

The required regularity exists: Buyers demand contractual terms compatible with relevant value optimal norms.

If almost all others demanded different terms, the buyer would conform to that demand.

- Unless you have a go at negotiate.

If you detect a norm-incompatible term and object to it, you reveal yourself as an incompatibility detector.

We are focusing on the no-negotiation cases.

But what happens when markets fall far short of contractual norm completeness because there arent enough value optimal norms?

We offered examples of both types of failures in earlier chapters.

We return to suboptimal norms at the end of the next chapter.

Lack of relevant norms is characteristic of pay-with-data exchanges.

An analogy from the late 1800s shows why.

Should one say, Hello?

(as Bell suggested) when answering a phone?

Who should be called?

They lacked shared conceptions of role-appropriate behavior as telephone users.

They arose over time out of repeated interactions.

We are in a similar situation with pay-with-data exchanges.

They will only evolve over time through patterns of social and commercial interaction.

Instead of shared conceptions of appropriateness, we have the intense controversy that surrounds behavioral advertising.

Only a few did.

The solution is to create the first-order, value optimal informational norms that we need.

We will show how to do so in the next chapter.

Notes and References

1.

The precise address is http://searchconsumerization.techtarget.com/news/2240160776/Apple-enhances-enterprise-mobile-rig-security-withbiometrics (visited August 6, 2012).

We generated the list using the Ghosteryadd-on for the Chrome internet tool.

IBM what is big data?

Bringing big data to the enterprise, accessed November 4, 2012, http://www-01.ibm.com/software/data/bigdata/

4.

John Gantz and David Reinsel.

The digital universe decadeAre you ready?

Big data: The next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity, 2.

Big data to drive a surveillance society.

Computerworld, March 24, 2011, http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9215033/Big data to_drive_a_surveillance_society

7.

FTC staff report: Self-regulatory principles for online behavioral advertising, February 2009, 2, www.ftc.gov/os/2009/02/P085400behavadreport.pdf

8.

Models may distinguish several more entities and functions.

See, for example, IAB Data Usage and Control Taskforce.

Data usage & control primer: Best practices & definitions, May 2010, www.iab.net/media/file/data-primerfinal.pdf

9.

- eXelate announces Invite Media partnership; CEO Zohar offers insights on data marketplace.

AdExchanger.com, January 26, 2010, http://www.adexchanger.com/data-exchanges/exelate-invite-media/

12.

- amNY special report: New York Citys 10 hottest tec startups.

amNewYork, January 25, 2010, http://www.amny.com/urbanite1.812039/amny-special-report-new-york-city-s-10-hottest-tech-startups-1.1724369

13.

Center for Digital Democracy.

Aperture, accessed July 14, 2012, https://datranmedia.com/aperture/audience-measurement/index.php?

Google makes up 20.28% of all the tracking on the web, while Facebook is 18.84%.

Less well-known trackers comprise the remaining 61%.

How unique is your web online window?

In Privacy enhancing technologies, Springer Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2010, 118.

Rocket fuel CEO John says ad exchanges more like a technology platform than media source.

AdExchanger.com, August 24, 2009, http://www.adexchanger.com/ad-networks/rocket-fuel-ad-exchanges/

18.

Western Electrician XXI (July 17, 1897): 3637.

Privacy in Peril: How We Are Sacrificing a Fundamental Right in Exchange for Security and Convenience, 183.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

7,500 Online shoppers unknowingly sold their souls.